Before I set out to interview poet and editor David Groff about his collection of poems, Clay (named for his husband, Clay Williams), l spoke with Charles Flowers, publisher of the queer literary journal BLOOM, and asked him about a good entry point for this interview. "Grief," he said. "In times of distress, people turn to poetry." While I appreciated his answer, he located grief in 9/11, an event that postdates the start of the AIDS crisis. However, it's not 9/11 but World AIDS Day (Dec. 1) that will occasion Groff's presentation, "Love in the Time of HIV: Poetry, Spirit, and Survival" at St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York City.

Before I set out to interview poet and editor David Groff about his collection of poems, Clay (named for his husband, Clay Williams), l spoke with Charles Flowers, publisher of the queer literary journal BLOOM, and asked him about a good entry point for this interview. "Grief," he said. "In times of distress, people turn to poetry." While I appreciated his answer, he located grief in 9/11, an event that postdates the start of the AIDS crisis. However, it's not 9/11 but World AIDS Day (Dec. 1) that will occasion Groff's presentation, "Love in the Time of HIV: Poetry, Spirit, and Survival" at St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York City.

This setting makes sense since churches, synagogues, and mosques have always served as staging areas for ceremonies commemorating life events -- birth (baptism), love (marriage), and death (funerals) -- themes interwoven through this year's Clay, Groff's award-winning collection of poems. With Clay Groff demonstrates a rare courage and brave urgency in how he approaches the Grand Emotions (Love, Hope, Fear) through the lens of autobiography, on the page unearthing language that distills grief, sex, and intimacy.

Tomas Mournian: The collection's title, Clay, is so everything -- evocative, erotic, mysterious. How did you chose it?

David Groff: I was lucky to fall in love with a man who had such a terrific, resonant name, one he graciously let me borrow. If he'd been named Bill, or Chad, the title might be different. Clay is the mineral and organic matter of the earth, the earth's gift from which we spin art, and the vessels of ourselves, which are made useful by fire that also renders them breakable. So the word was not only the moniker of my partner of 17 years but a totem I could bear into the larger world.

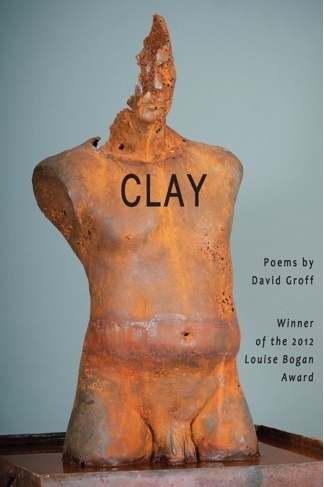

Mournian: Did you choose the cover image of Clay, Clinton T. Sander's photograph of sculptor Michael Brohman's disintegrating male torso?

Groff: Yes. Michael and I were residents together at the Santa Fe Art Institute. When I saw his sexy, earthy art, I knew that I wanted an image of his work on my book cover. I love his sculpture's rust and robustness.

Mournian: What is Clay's organizing structure?

Groff: Clay starts in a difficult place, with a hard question: How do we love when we're relentlessly aware of death's impending presence? Each poem is a step on a twisting path that I think ultimately leads to a happier, or at least more resolved, place: a beach, a memory of meeting, a marriage.

Mournian: How did your partner's Buddhism influence poems like "Clay's Cough," "Dread," and "Epithalamion," reminders about the constant presence of death in life?

Groff: I'm not a Buddhist; I'm too attached to my anxiety. But Buddhism slips into my poems, not only in the form of a memento mori but as a reminder of life. For example, Clay taught me what became in "Epithalamion" the book's final, very Buddhist image: a wave returning to the ocean that made it.

Mournian: Yet despite its melancholic tone, there are poems in the collection -- the bitingly funny "Milton," the bitchy "Last Call," the weirdly erotic "Musculature" -- that contrast with the collection's darker tone.

Groff: Whether they're encountering coffee-shop culture, the sometimes-irksome persistence of our poetic great-uncle Frank O'Hara, or a furious fly disturbing two lovers, I hope readers can find some fun.

Mournian: "My Father, a Priest, Pruning" made me wonder if his presence in your poems has always been so gentle or if it evolved.

Groff: My father is drawn like a poet to the beauty and assurance of the Episcopal faith. I lack his confidence but am attracted to it and seek relief in it. In my poem "A Boy and His God," the Supreme Being is a homeless magician plucking a dead rabbit out of his hat. Sometimes I want to belong to God like a Mormon with a name badge and a finger on your doorbell. But for me that's not the truth that the body tells us.

Mournian: Reading "To Men Dead in 1995," I thought about the more recent death of activist Spencer Cox. How would you characterize a post-AIDS-crisis generation?

Groff: I'm especially obsessed with the fate of my friends, many of them brave activists, who died in the mid 1990s, just before the new generation of drugs turned certain other people with AIDS into Lazaruses. I've been working on a couple of poems about Spencer. I hope that we can address, in our lives and art, the epidemic of depression, the costs of survival, the legacy of loss, and the need to make sense of what we endured.

Mournian: Reading Clay, I kept hearing Amy Winehouse's "Love Is a Losing Game." To what extent does popular culture inform your poetry?

Groff: We're all part pop. In the book's title poem, set in Sedona, Ariz., "TV has-been Glenn Scarpelli banshees / O Holy Night into an evening wholly empty." There's surprising poetic power in the proper, popular name.

Mournian: Why do you believe this moment, 2013, invites people to look back at that era in a way that perhaps we could not have done before?

Groff: As happened in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, we exile a great trauma from our cultural imagination for a while, at great detriment to those affected by that trauma. When the wounds scar over somewhat, we can bear to behold them again. Yet the great works about cataclysmic events, books like The Red Badge of Courage or War and Peace, sometimes don't appear for a generation or more.

Mournian: James McBride, the winner of the National Book Award for Good Lord Bird, recently said of Paul Monette's coming-out memoir, Becoming a Man, "I've often thought to myself, if they took the graphic sex scenes out of that book, it could be required reading in public schools."

Groff: I was the editor of Paul Monette's last two novels. I just wish his work had more graphic sex scenes.

Mournian: How would you compare Paul Monette, a poet who wrote about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in real time, from the epicenter, and died of AIDS-related complications in 1995, with poet Thom Gunn's "The Man With Night Sweats"?

Groff: Monette wrote cascadingly furious poems of grief; he radicalized the elegy. His poems haunt me, but I think I actually share something of Gunn's wry angle on love and lament.

Mournian: You often speak about being a "good literary citizen." What do you think the future holds for a queer literary community given its balkanized state?

Groff: This summer I led a poetry workshop for emerging queer writers. I was dazzled by the vitality, urgency, and propulsively public engagement of the writers there. They have so much talent; they have so much fresh stuff to say. As LGBT identity evolves, perhaps beyond any current recognition of it, LGBT writers will remain in the vanguard, leading us all to new understandings of gender and sexuality, power and justice, loving and dying.